Closing the Loop

...Such an Office Space Title This Time...But Necessary

Engineering Manager Public Safety Announcement: As I wrote this Substack post today, I wanted to make a public safety announcement for managers. It is incredibly easy to turn this mechanism into a culture and morale-destroying habit. Part of the discussion also has to be, “Is closing this loop worth the trouble?”

Just be careful out there. Not all loops are worth closing - please prioritize loop closure based on customer impact, not politics.

The $2 Trillion Problem Nobody's Talking About: Why Your Best People Can't Close the Loop.

Let me tell you something that'll make your quarterly board meeting feel like a poetry reading at a funeral. We're burning $2 trillion annually—that's trillion with a T, as in "the GDP of Italy"—because we've collectively forgotten how to finish what we start.

Every 20 seconds, another million dollars vanishes into the ether of incomplete projects, half-baked features, and that special purgatory where good intentions go to die.

Day one at Amazon, my manager, Rob Francis—now CTO of Booking.com—pulled me aside. "Close the loop," he said. Three words that changed how I think about everything. Not "work hard," not "be innovative," not "think big."

Close. The. Loop.

You know what Andy Grove said? A manager's output encompasses the output of their organization, as well as the output of the neighboring teams they influence. Grove built Intel into a semiconductor empire with that philosophy, while the rest of us measure success by how many meetings we survive. Here's the kicker: 66% of software projects fail. Two-thirds!

If surgeons had that success rate, we'd all be learning home remedies from YouTube.

We've got ourselves an epidemic of open loops

The data's staring us in the face like a disappointed parent. Standish Group's CHAOS report—and they didn't name it that because they're optimists—tells us only 31% of IT projects end successfully. The rest? They're either canceled outright (31.1%) or limping across the finish line over budget, past deadline, with half the promised features. Meanwhile, we're sitting in retrospectives, wondering why our velocity charts resemble an EKG during cardiac arrest.

Here's what kills me: 45% of features in software projects are never used. Never! We're literally building digital ghost towns. Pendo's research shows 80% of product features gather dust like your grandmother's china. Would you like to know the real tragedy? Microsoft Office users typically utilize only about 5% of the available features. Five percent! We've built the software equivalent of a Swiss Army knife when people needed a butter knife.

Peter Drucker foresaw this in 1954 when he introduced Management by Objectives. Clear goals, measurable outcomes, regular reviews—revolutionary stuff that we've somehow managed to complicate into oblivion.

The man gave us a roadmap, and we turned it into a Jackson Pollock painting.

Amazon figured out what the rest of us are still googling

In 2010, Amazon had 452 detailed goals. You know how many times "revenue" appeared? Eight. "Free cash flow"? Four. "Net income," "gross profit," "operating profit"? Zero, zilch, nada.

They cracked the code: measure inputs, not outputs.

You can't control your stock price, but you can control how fast you pick items in a warehouse. Unfortunately, you can't promise revenue, but you can make sure a timely response to customer service. They call it "Working Backwards"—start with the press release announcing your product's success, then figure out how to make it real. Brilliant in its simplicity, which is probably why most companies can't do it.

Their Weekly Business Review isn't about celebrating vanity metrics; it's about obsessing over controllable inputs. While your competitors are staring at revenue dashboards as if they're reading tea leaves, Amazon is measuring pick-and-pack efficiency in milliseconds.

However, what most people miss is that Amazon applied a relentless cadence to closing loops. "You'll get back to the S-Team by the end of the day." "We'll schedule a follow-up with Andy next week." Specific commitments with specific timelines. They injected urgency without becoming abusive, though I'll admit, sometimes that line got crossed when teams got derailed from their original purpose, chasing someone's pet metric.

Another famous example: The CEO sends a customer complaint with just a “?” as the content of the note, expecting an answer by the end of the day.

The dreaded question mark was an example mechanism for diving deep, demonstrating customer obsession, and auditing work.

However, if I had a penny for the number of times it derailed or demoralized a team… it is a powerful tool which must be used wisely young paduan.

Google borrowed a page from their OKR system—70% completion is considered success because they're aiming for the moon. They deploy code 200 times more often than traditional companies. Their problems get fixed 24 times faster. You know why? Because every key result has a designated owner, verifiable evidence of completion, and transparency that would make a government whistleblower envious.

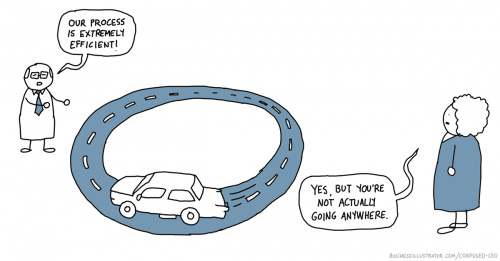

The difference between motion and progress

Let me paint you a picture with numbers, because anecdotes are for people who can't do math. McKinsey found that large IT projects run 45% over budget and deliver 56% less value than promised. BCG reports that 70% of digital transformations fail—seven out of ten. You'd have better odds at a casino, and at least they'd comp your drinks.

Why? Because we've confused being busy with being productive. Jim Collins called it disciplined execution—you need disciplined people having disciplined thoughts taking disciplined action. Instead, we've smart people with scattered thoughts, taking random actions, and then wondering why our flywheel looks more like a flat tire.

Beware of AI, as it only makes it easier to avoid closing a loop. It can be an extraordinary tool to inject into mechanisms to ensure loops close, but it can also “volunteer” and generate immeasurable loops.

They don’t call it generative AI by accident.

Here's the brutal truth: "closing the loop" isn't just about getting work done. Too often we internalize it as "personally check on an objective and finish it." But ask yourself—what happens when you're not there?

I sometimes get hospitalized, which means taking time off work. If the loop only closes when I'm physically present, it's not a system—it's a single point of failure.

Real loop closure requires mechanisms, not miracles. (I've written extensively about this here:

A mechanism runs without you.

A mechanism doesn't care if you're in the hospital, on vacation, or got promoted. Good intentions are what you have before you build a mechanism. Mechanisms are what actually close loops.

Here's the framework that actually works, and I'll spare you the consultant speak:

Input Goals vs. Output Goals—the Amazon model that everybody talks about but nobody implements. Output goals are what you want: increase revenue 20%, reduce churn 15%, achieve world peace. Input goals are what you control: make 10 customer calls daily, ship code twice a week, exercise three times before breakfast.

You measure both, but you manage inputs. It's like fitness—you can't control losing 40 pounds, but you can prevent eating 1,800 calories and walking 10,000 steps. One is a wish, the other is a plan.

How managers need to become completion auditors

Grove's High Output Management isn't just a book; it's a manual for excelling at your job. He used paired indicators—measuring both quality and speed, as well as efficiency and effectiveness. You push one metric, you watch its counterpart like a hawk.

It's management by peripheral vision.

But here's what separates great organizations from the rest: modeling the behavior down your leadership chain. When your director closes loops diligently, managers learn to do the same. When managers close loops, team leads close loops. When team leads close loops, individual contributors close loops. Culture isn't what you preach—it's what you repeatedly do until it becomes muscle memory three levels below you. DNA replication is essential.

Modern tools give us dashboards that'd make NASA jealous, but we use them like expensive screensavers. You need:

Weekly Completion Reviews: Not progress updates—completion audits. What's actually done versus what's "basically done" (which is manager-speak for "not done"). Product owners reviewing task status, teams demonstrating working functionality, and stakeholders providing feedback that matters. And critically, have your skip-level reports present their loop closures. Nothing teaches accountability faster than watching your boss's boss consistently follow through. Warning signs? Consistently incomplete sprints, "done" work that would embarrass a summer intern, teams dodging demos like they owe them money.

Definition of Done that actually defines done: All code reviewed, tests passing with >80% coverage, documentation updated, security scans completed, performance benchmarks met, stakeholder acceptance received. Not suggestions—requirements. Non-negotiable gates between "worked on" and "working."

Digital MBWA (Management by Walking Around): Random Slack check-ins that start with "How can I help?" not "Where's my report?" Virtual coffee chats, open office hours, sitting in on standups. You're removing roadblocks, not installing surveillance cameras.

Crucially, in early-stage startups, incentives are often the problem. Nobody is getting paid, equity is virtual, and the belief in the mission may not be enough. What did I learn?

If you are having trouble closing loops in early-stage startups, kill the startup.

How employees need to work backwards from outcomes

Harvard Business Review published research showing that only 55% of middle managers can name one of their company's top five priorities. Fifty-five percent! We've built organizations where half the people don't know what game they're playing.

Before starting anything—and I mean anything more complex than making coffee—employees need to answer:

Who benefits explicitly from this work?

How does the customer benefit specifically? Trace the benefit all the way back to the customer.

What problem does this solve that alternatives don't?

How will we measure success from the user's perspective?

What business metric improves and by how much?

What happens if we don't do this?

Amazon's PR-FAQ method works because it forces this thinking upfront and forces working all the way back to the external customer benefit. Write the press release for your finished product. Include customer quotes. Add an FAQ addressing every "but what about...?" question. It's your North Star, your constitution, your "this is why we can't have nice things" when someone suggests scope creep.